Thucydides, Spreadsheet Phil and the coming Crash

An imminent stock market crash is more likely than investors might suppose. My recurrent nightmare this summer, partially informed by the modern Thucydides, (of whom more below) is that a stock market correction will begin in London when the Brexit negotiations collapse, possibly as soon as late October. But there is no longer such a thing as country-specific market risk: a seizure in London will swiftly infect the entire world…

Summertime, and the living is easy – or maybe not…

Mrs May is away hiking. One hopes the lady will have moments of repose. Meanwhile, a low-burn civil war has broken out within the British cabinet about our Brexit options. Chancellor Philip Hammond’s preference for a transitional arrangement (neither in nor out) has gained traction – but there are forces arraigned which are bitterly opposed to this.

The papers are full of tittle-tattle of the who said what to whom variety. The substance of the matter is that Mr Hammond and others believe that there is insufficient time between now and D-Day (29 March 2019) to negotiate and agree the terms of Britain’s exit from the European Union and to negotiate a free-trade deal as a third party state – not to mention to have both of these packages endorsed by the European Parliament and all the 27 national parliaments of the member states.

Failure to reach a deal will result in a so-called Crash Brexit whereby the UK reverts to WTO commercial rules on D-Day, thus potentially disrupting supply chains, particularly in Britain’s critically important automotive and aerospace sectors. Therefore, the Hammondistas argue, we should plan for a transitional period of two years or so after D-Day in which, effectively, the UK remains in the EU until such time as the post-Brexit landscape is determined.

I explained exactly why investors should be fearful of a Crash Brexit in my piece in these pages on 23 June – the first anniversary of the UK referendum. I called the proposal for a transitional period TRemain (temporarily remain). Readers may therefore infer that I am broadly in support of Mr Hammond. But I also have sympathy with his detractors because they rightly foresee that TRemain could be used as a ruse to hold the UK in a state of limbo indefinitely or – even worse – to reverse the Brexit process altogether.

Tory MPs like Jacob Rees-Mogg remind us that the UK is either in the EU or it is out. Failure to secure control of the nation’s borders – that is to terminate freedom of movement – and to break free of the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice (ECR) on D-Day would be a betrayal of the verdict of the British people, they argue. Within cabinet, Messrs Johnson and Fox are thought to favour a clean break with the EU on D-Day regardless of the (temporary) consequences in terms of disruption of supply chains. Their view – articulated by the increasingly influential Mr Rees-Mogg – is that since nearly half of our total international trade is already conducted seamlessly under WTO rules, there is little to fear.

TRemain could be used as a ruse to hold the UK in a state of limbo indefinitely or – even worse – to reverse the Brexit process altogether.

At the time of writing Mrs May appears to favour the end of freedom of movement on D-Day, which implies that she is opposed to a transitional period or TRemain and wishes to stick by the roadmap set out in her Lancaster House speech of 17 January. The fact is, however, that her authority has been greatly undermined since she lost the Conservative Party its majority in the House of Commons at the General Election. The only reason that she has survived as PM is that the parliamentary party believe that a leadership election at this juncture would only weaken Britain’s negotiating hand with our EU counterparts. Many – possibly most – Tory MPs believe that she is no more than a caretaker leader. Therefore what she believes on any topic will not necessarily carry the day.

Moreover, the entire dynamic of the Brexit negotiations changed in late July. Before substantive trade discussions can be initiated in the autumn it was always going to be necessary to resolve three core issues. Namely: the status of EU citizens resident in the UK (and correspondingly that of British citizens resident in the EU); the question of the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland; and the little matter of the “Brexit bill” – the monies supposedly owed by the UK to the EU in respect of projects to which the UK had already pledged financial support.

I had supposed that, given goodwill and good preparation, these three matters would be put to bed by October. I wrote to that effect at the end of March when I still thought an amicable divorce was possible. Yet, when Michel Barnier summed up the negotiations so far in late July, it was clear that both sides were far from occupying common ground on all three issues. The Europeans have introduced spoilers on every count. UK-resident EU citizens’ rights at work should continue to be subject to the ECJ. (As if Europeans working in, for example, Japan, should be protected by a foreign court). The Irish border should be extended to the Irish Sea (meaning that Northern Ireland would have a border with the mainland UK). The UK should pay up sufficient funds to honour programmes from which it shall never benefit. And so on.

Regarding the Brexit bill, according to a recent ICAEW briefing paper[i], a reasonable net exit charge is likely to be much lower than the more extreme projections of up to €100 billion once the money due back to the UK is accounted for, ranging from a low of £5 billion up to a maximum of £30 billion, with a central scenario of £15 billion. One wonders if Monsieur Barnier has read the paper.

On my reading, despite Mr Davis’s upbeat language, the Brexit negotiations have gotten off to a discouraging start. They may fall apart completely as early as October. The idea that everything will be signed and sealed by D-Day is fanciful.

Additionally, Frau Merkel enters the German election campaign this month more convinced than ever, like Voltaire’s Candide, that the Eurozone architecture represents the best of all possible worlds – and the new French President seems to be unable to restrain her. The Greeks and others who have argued for comprehensive debt relief have been effectively suppressed, so the fundamental imbalances inherent in the Eurozone – where surplus countries heap up more surpluses and indebted countries accumulate more debt – are likely to be perpetuated. She is certainly not in a mood to accommodate British exceptionalism.

If we wish to know just how impossible negotiating with the EU can be, we should consider Greece’s experience.

Britain is in a much stronger position than Greece, but if we wish to know just how impossible negotiating with the EU can be, we should consider Greece’s experience.

Reflections on a Greek tragedy

My holiday reading has included Adults in the Room by superstar Greek economist Yanis Varoufakis. Yanis (I am sure he would not object to my familiarity) was an academic economist in the UK, Australia and the USA and already a well-known commentator internationally when he was appointed Greek Minister of Finance in the radical government of Alexis Tsipras in January 2015.

Now I fully admit that Yanis is a leftie who believes inter alia that the cure for modern ills is a massive redistribution of wealth along socialist principles. But in his diagnosis of those economic ills he has attracted wide admiration from the libertarian right, who like him believe that if there are irresponsible borrowers there were highly irresponsible lenders. Yanis has a profound understanding of how the modern international financial system works. Brexiteers like Norman (Lord) Lamont use his critique of how the European Union works as justification for their Eurosceptic position; though Yanis aspires not to Grexit but to a “true European Union” in which the rich countries (Germany) adopt a more generous stance towards poor ones (of which, Greece).

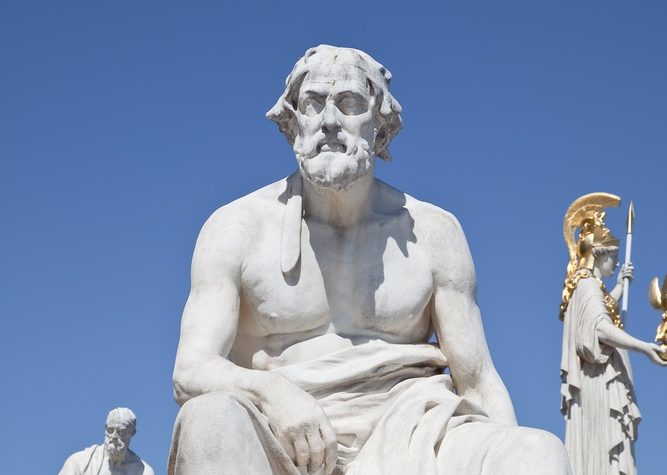

Columbia’s professor of economics Jeffrey Sachs has described Yanis as “the Thucydides of our time”. The author of the History of the Peloponnesian War (which ended in 404 BC) was the first historian of the ancient world to adopt scientific history – in other words he rationalised the affairs of men without attributing victory and defeat to divine intervention, as did his predecessors (like Herodotus).

The main message of the modern Thucydides is that the so-called Greek bailout of 2010 was not a bailout of the admittedly bankrupt Greek state but of the French and German banks. These had built up massive exposures to the Greek private and public sectors over the previous seven years on the crazy assumption that all Eurozone borrowers were of more-or-less equal risk. A Greek state default would have triggered a wave of bankruptcies in the Greek private sector. In aggregate, the major French and German lenders – amongst them Société Générale (EPA:GLE), BNP Paribas (EPA:BNP), Commerzbank (ETR:CBK), Deutsche Bank (ETR:DBK) – would have gone bust or at least been rendered zombies. That, in turn, would have necessitated massive bank bailouts by the French and German governments which would have wrecked their national finances.

There was initially a technical problem. Under the Maastricht Treaty (1992), which established the architecture of the common currency, the European Commission may not lend directly to the government of a member state. As usual, the EU mandarins found a way around that. The new loans would not be “European” but “international” by co-opting the IMF into the deal. In fact there would be a Troika of the EU, the ECB and the IMF. The IMF’s involvement was facilitated by its then President, Dominique Strauss-Kahn. Strauss-Kahn at that point was expecting to be President of France within two years and was more than happy to oblige.

The so-called Greek bailout of 2010 was not a bailout of the admittedly bankrupt Greek state but of the French and German banks.

Yanis is too well-mannered to mention that Strauss-Kahn fell from grace in May 2011 and had to resign both as IMF President and French presidential candidate when he was interrupted in a Washington hotel room in compromising circumstances. (Greek tragedy once again: or perhaps comedy, depending on your nature). He was immediately replaced by the then French Minister of Finance, Christine Lagarde – who proved an even more determined advocate of the interests of the French banks.

The solution offered was to pretend that the Greek state was not facing a solvency crisis but a liquidity crisis. (This is a common ruse in international banking). With a loan of €110 billion, together with a rigorous package of austerity measures affecting flibbertigibbet Greek pensioners and public sector employees, everyone else could continue as if nothing had happened. The outcome was that Greece was plunged into a massive economic contraction just as its debt inflated: the country became economically unviable. Much of this “bailout” (a neologism coined during the financial crisis) was dressed up as bilateral loans between Eurozone member states. (Though, the likes of Slovakia and Ireland had no idea that they were in fact using state funds to bail out the French and German banks).

In normal circumstances Greece should simply have declared itself bankrupt – something most European countries have done over the last 200 years multiple times. No rational lender would make new loans to a country whose governments, banks, companies and households were all insolvent at once. Instead, it was kept alive in a kind of economic living-death in order for the large countries and the ECB to continue business as usual. By the end of 2011 the economic condition of the country had declined even further and it was clear that unless further funds (another €130 billion) were injected into the patient’s veins, the first bailout would have been for naught.

Between the first and second Greek bailouts the French and German banks had been permitted to sell down their Greek exposures, mainly to the ECB itself, now under the reanimated leadership of Mario Draghi. The ECB simply printed Euros to cover its positions – once again against the original rules. The second time around, however, the Troika insisted that Greek debt should now be subject to a haircut (the bankers’ word for a write-down in value). But that haircut would mainly be applied to Greek pension funds, state institutions, and domestic Greek savers (including pensioners) who had bought Greek government bonds. Loans provided by the Troika remained inviolable.

Moreover, €50 billion of the €130 billion second bailout was put into a recondite fund – the Hellenic Financial Stability Fund (HFSF) – which the Greeks would have to repay, though over which the Greek Parliament would have no scrutiny whatsoever. Since that time a spiders’ web of stability funds has been spun across Europe and very few people know who controls them – certainly not the European Parliament, as I wrote in May last year.

In return, the Greeks were forced to slash public expenditure by up to 20 percent – a degree of “austerity” that Ms Sturgeon and Mr McDonnell could not imagine. The Greek economy contracted by even more than that.

The Greeks behaved supremely improvidently after they were admitted to the Euro in 2003 – but who let them in, and who lent them all the money?

When Yanis finally became Greek Minister of Finance in January 2015 he spent his six months’ tenure trying to persuade the EU powers that be – especially Germany’s finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble – that the only way forward was a judicious debt restructuring: only to have doors slammed in his face. Eventually, Schäuble & Co. squeezed PM Tsipras to have Yanis removed – even though the Greeks had just voted for his proposals in a referendum.

If you go to Greece this summer and wonder why all the provincial museums are closed, why people with professional qualifications are homeless and why there are hundreds of thousands of children living in poverty – the answer is, quite simply, Europe. Of course, the Greeks behaved supremely improvidently after they were admitted to the Euro in 2003 – but who let them in, and who lent them all the money?

Lessons learnt from the Modern Thucydides

The first lesson is that the EU always makes up the rules as it goes along precisely in order to protect the interests of the EU generally and those of its central drivers (Germany and France) in particular. The second is that the EU would rather that people suffer – as the Greeks did – than that any European institutions be compromised. The third is that, ultimately, what Europe’s interests are is a matter determined in Berlin.

The European budget conundrum

It is therefore of concern that recent noises coming out of Berlin regarding Brexit have sounded extremely uncompromising. All this makes the likelihood of an amicable divorce very slim.

Barnier, Verhofstadt, Juncker & Co. continue to speak as if all this is a purely British problem; but in reality it is very much a European problem. The main reason why the EU mandarinate are so concerned to extract the largest Brexit fee from the UK as possible is that they understand very well that post-Brexit, assuming no further UK annual contributions, the EU budget will be blown apart.

What this means in practice is that literally thousands of town halls (one should say hôtels de ville, Rathäuse, ayuntamientos etc.) will have to abandon their plans for more bread and circuses for the European masses which are paid for by generous EU handouts in return for their compliance. The cessation of those transfers could even provoke mass populist disruption. Irish EU Agriculture Commissioner Phil Hogan thinks that the remaining members will either have to spike their contributions unacceptably or receive much less[ii]. The Germans, for their part, have made it clear that they are loath to pay more. Moreover, the UK’s departure from the bloc will expose multiple fissures which have been long covered over.

By late October all will become clear.

By late October all will become clear. The no-deal scenario will damage both sides. But it is Frau Merkel who is driving the European people’s car towards the cliff edge with Mrs May sitting in the passenger seat – like Thelma and Louise. We are heading for a disruptive parting of the ways between Britain and Europe which, as in Greek tragedy, is ineluctable – determined by semi-divine forces beyond the control of the individual actors: unless all can be resolved by some unexpected deus ex machina. Each protagonist believes himself to be righteous and good; and solely motivated by reason. As ever in Greek tragedy, all parties will suffer.

And finally…

Shortly I shall explain why Mr Trump’s increasingly impotent administration coincides with a moment of dramatically increasing geopolitical risk, which is likely to undermine the US stock market soon. There are also reasons to be sanguine about the Chinese economy and there are some very worrying jokers in the pack. (One of them is called Kim.) I’ll explain the mechanism whereby the Brexit crash could be translated into a systemic global market crisis. It is time for investors to take a defensive stance.

I really didn’t want to ruin your summer – nor mine. So having got that off my chest, I’m heading back to the pool with a good book. It’s a fat tome by a chap with a silly name – something about a war in ancient Greece in the fifth century BC – caused by the break-down of an alliance – which ended badly for both sides…

[i] Institute of Chartered Accountants in England & Wales, The EU Exit Charge, available at: https://www.icaew.com/-/media/corporate/files/technical/economy/brexit/eu-exit-charge.ashx

[ii] See: http://www.express.co.uk/news/world/835020/Brexit-news-EU-budget-cuts-Phil-Hogan-UK-departure

This is a real doomsday book.

Victor Pleased to see that someone has translated Yanis’ brilliant expose of the EU duplicity in dealing with Greece (as described in Adults in the Room ) into the Brexit scenario.

The most important lesson learned by Yanis was the impossibility of negotiating a debt repayment if the lending doesn’t care if they get their money back.

Reading the book made me realise the EU will be ruthless in ensuring no other member will risk leaving the EU by making Brexit extremely painful for the UK even if it also damages their own economy.

An advertising campaign in European newspapers pointing out that we import far more from the EU than we export to them could be effective. Just point out to their citizens, as the German elections come close, what is going to happen to their car industry, wine producers etc. if we decide to take the no deal option and just leave.

Good stuff. Cuts through the fog nicely.

The most intelligent, warts & all summary I’ve read