Is this the end of the ‘golden age’ of air travel?

Victor Hill investigates which airlines will survive in the post-pandemic world? Is this the end of the ‘golden age’ of air travel?

The global airline industry has been particularly hard hit by the lockdowns imposed in response to the coronavirus pandemic. Borders have been closed and whole fleets of aircraft have been grounded for much of Q2 2020. Moreover, even when the lockdowns are substantially relaxed, demand is likely to be subdued, as people who have lost income postpone holiday plans or opt for a ‘staycation’. A number of airlines will fold. But those that survive will benefit from reduced competition and possibly higher margins. Some airline stocks therefore have the potential to rebound, post-pandemic.

Times of trouble

Even before the coronavirus pandemic became a reality in late February, a number of major airlines were in difficulty. Flybe, the British regional airline, was declared bankrupt on 5 March. And Norwegian (OTCMKTS:NWARF), the long-haul budget operator which is the third-biggest airline at London Gatwick was thought to be on the brink.

On 20 April, Norwegian Air announced that four subsidiary companies supplying it with pilots and cabin crew in Sweden and Denmark had filed for bankruptcy. The move put nearly 5,000 jobs at risk. The airline had already cut 85 percent of its operations, and grounded all but 11 planes in its fleet of 160. Lenders to Norwegian voted in late April on whether to convert up to £3.5bn of loans and lease commitments into equity. That would require the consent of a shareholders’ meeting on 5 May before €300m of emergency funds could be made available by the Norwegian government.

I am writing this in late April, in the fifth week of the UK lockdown. Although some European countries and American states are beginning to relax their lockdowns in important ways – for example, Spain is allowing children to play outside for the first time in seven weeks – we are still very far from ’normality’. In fact, something that most of us have taken for granted – the ability to book an economical flight with a leading budget airline such as easyJet and jump on it a few days later – is no longer available to us.

There is a deep-seated fear that the ‘golden age of air travel’ might already have slipped away. Nearly 69 million flights took off around the world in 2019 according to Flight Radar – that’s about 189,000 every day. How many will take off this year? We just don’t know − probably many fewer.

It’s true that the progress of commercial aviation has not always been smooth. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks of 2001, US airspace was closed for nearly a week and was only reopened after stringent new security measures were introduced. Then, after another failed terrorist attack in 2006, security measures were upped further. Yet we soon become used to taking off our shoes and being scanned at airports – and to removing liquids from our hand luggage. But this time changes are afoot which may change our attitude towards flying altogether.

On 16 April, easyJet’s chief executive, Johan Lundgren, announced that his airline would be unlikely to sell the middle seats on its planes when flights resume. Providing an empty seat between passengers sitting in the window seat and the aisle would facilitate a degree of social distancing.

That will change the economics of air travel. easyJet’s business model hitherto – like that of other budget airlines – has been to maintain very high load factors (ie sell as many seats as possible on every flight – very often the flights are full) and to ‘sweat the assets’, by keeping its planes in the air most of the time. For example, the same Airbus A320 flies from Gatwick to Toulouse five times a day, seven days a week. It is in the air as long as it is on the ground. But from now on, the load factor will not exceed two thirds. That inevitably means that air tickets will become more expensive – or at least that the ultra-cheap tickets which are relatively common on Ryanair will become a thing of the past. Ryanair dismissed Mr Lundgren’s proposal as unworkable.

Whether air traffic will ever recover to 2019 levels is uncertain; and in the meantime many airlines will need emergency funding of one kind or another to survive. A recent report by Forbes estimated that up to $1trn could be required to bail out the global airline industry.

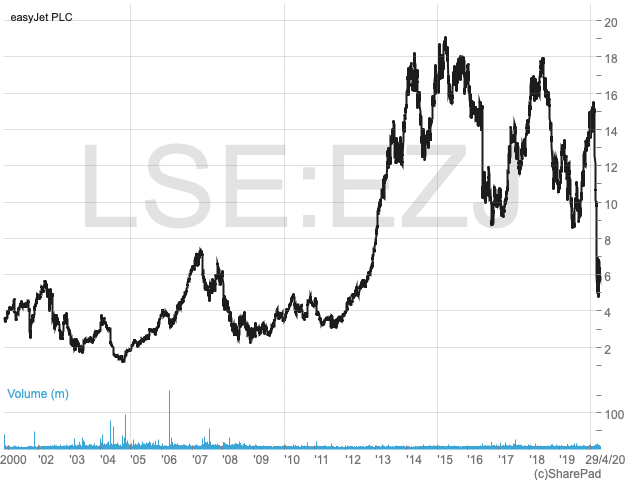

easyJet (LON:EZJ)

easyJet was performing well before the pandemic became manifest in mid-February and has a good chance of weathering the storm. It was the first major airline to secure a Bank of England-guaranteed loan in the order of £600m under the UK government’s Covid Corporate Financing Facility (CCFF).

On 27 April easyJet’s senior management urged investors to reject a boardroom coup instigated by the airline’s founder and biggest shareholder, Sir Stelios Haji-Ioannou. Sir Stelios wants to remove John Barton, chairman and chief executive Johan Lundgren as well as two other directors in a row over a £4.5bn contract with Airbus. The motion will be put to a vote on 22 May.

The Golden Age of Air Travel

Commercial aviation began way back in the 1920s with Qantas (Queensland and Northern Territories Airline Service) one of the very first airlines. But in the years from World War II up until the 1980s the airline industry was entirely dominated by state-owned ‘flag-carriers’, many of which offered notoriously poor levels of service. We can point to the US Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 under President Carter as the beginning of the ‘golden age of air travel’. This permitted privately owned airlines to enter the US commercial aviation market for the first time – a measure that, in due course, was replicated across the world. Under the Thatcher government in the UK (1979-90) the airline industry was further deregulated, with British Airways being privatised and listed on the stock exchange for the first time in February 1987. In 1985, the Schengen Agreement loosened border controls within the EEC/EU. Most European countries privatised their flag-carriers in the 1990s and the first decade of this century. A number of ’budget’ airlines were launched and failed in the US in the early 1980s but it was Ryanair (founded in 1985 as part of an airline leasing operation in the Republic of Ireland) and easyJet (founded 1995) which really ushered in the era of cheap, efficient air travel. Both of these pioneered the internet-only model whereby customers now print off their own boarding cards or just display them on their smartphones. These two airlines, while remaining short-haul operators, taught the industry − including long-haul operators − how to strip much of the cost base out of air travel. Whether that golden age is now over is a question only time will answer.

Refunds on cancelled flights

Anecdotally, a lot of people who had booked tickets on flights cancelled during the lockdowns have not been refunded. The great feature of the airline business model is that customers pay up front, often well before travelling, so that airlines carry large amounts of freely financed working capital on their balance sheets. The trade body ABTA (Association of British Travel Agents) has lobbied the UK government to relax the rule that customers be refunded their cash within 14 days of cancellation for fear that half the airline industry may be at risk of collapse. easyJet has argued that customers are happy to receive a credit note in lieu of a cash refund – but how to obtain one is not always straightforward. We can be sure that there will be years of litigation ahead arising from compensation claims – an unwelcome and potentially costly drag on resources.

Coping with social distancing at airports

As I write this in late April, it is clear that even when the lockdowns in Europe and North America are substantially relaxed, social distancing is likely to continue indefinitely. This means much more than the demise of the handshake and the social kiss: it means that people will be discouraged from sitting close and mingling with one another. But at a crowded airport like Gatwick it will be almost impossible to keep two metres away from every other passenger while checking in and getting to the departure gate. That means that many people who either have not yet contracted the virus, or who consider themselves vulnerable due to underlying chronic conditions, may choose not to travel by air at all. Some older people, especially the over 65s, will prefer no-fly cruises – although the experience of passengers on the Diamond Princess and other cruise liners may have dampened enthusiasm even for that option. We can expect that the wearing of face masks at airports (and indeed on flights) will become mandatory. Passengers flying on Emirates out of its Dubai hub airport are already being tested for Covid-19 – and receiving the results of the test within 10 minutes.

Once passengers arrive at their destination airport they should expect to be screened, most commonly by having their temperatures taken by the now ubiquitous ray-gun thermometers. Japan and Hong Kong have been testing all new arrivals for Covid-19 since January. Those who test positive are taken to hospital immediately. Many countries – including now the UK – will require incoming visitors to go into quarantine for at least 14 days. This will further discourage and deter holidaymakers. That is why the trade association for the hotel booking industry (HBAA) has already asked the government to extend the UK’s furlough (employment retention) scheme for the hospitality sector well beyond June. Though a market might emerge for ‘quarantine resorts’. Another trade body, Airlines UK, said: “Nobody is going to go on holiday if they’re not able to resume normal life for 14 days”.

As I write, Gatwick’s north terminal is still closed and Heathrow – which wanted so recently to build a third runway – is operating with just one runway. I have been saying for some time now that while flying has been getting more bearable, the airport experience has been getting much more disagreeable. That trend is likely to accelerate − and will be a long-term disincentive to travel by air.

Virgin Atlantic & Virgin Australia (Private)

On 20 April Sir Richard Branson said that his airline, Virgin Atlantic, would collapse imminently without emergency funding. He even said he could use his private island, Necker, in the British Virgin Islands, as security for any government loan forthcoming.

The next day, Virgin Australia, which is only 10 percent owned by the Virgin Group, went into voluntary administration under Deloitte. Much of its 94-strong fleet had already been grounded in the wake of Australia’s closure of its borders in early April. The airline had asked Canberra for AU$1bn of support, but was refused – much to Sir Richard’s chagrin. None of the existing shareholders were in a position to help. That includes HNA (SHA: 600221) the struggling Chinese conglomerate, Etihad Airways, which has been prepared to let other overseas investments fail; Singapore Airlines (SGX: C6L), which has just received its own bailout; and Nanshan Group (SHA: 600219), owner of China’s Qindao Airlines.

As I write there are efforts to recapitalise Virgin Australia and to reboot its domestic operations. The company owes at least AU$7bn (£3.5bn) to creditors, including around AU$450m to its 10,000 staff. Although Virgin Atlantic and Virgin Australia have vastly different ownership structures and route networks, Virgin Australia offers a template for what might happen if the same fate were to befall Virgin Atlantic.

Sir Richard apparently needs about £500m to keep Virgin Atlantic going. He co-owns Virgin Atlantic through the Virgin Group with the US airline Delta (NYSE:DAL) which holds a 49 percent stake. Delta bought that stake from Singapore Airlines in 2013.

The problem is that Virgin Atlantic has few tangible assets, as nearly all of its aircraft are leased and its take-off and landing slots at Heathrow (and elsewhere) have already been mortgaged. It has debts of reportedly about £1.5bn. The veteran entrepreneur said that without Virgin Atlantic, British Airways would dominate transatlantic air travel, there would be less competition and thousands of jobs would be lost. (The airline employs nearly 10,000 people). Virgin has appointed the London-based restructuring specialist Houlihan Lokey to help find a way out. Houlihan Lokey has reportedly sounded out about 50 potential investors, including the hedge fund Lansdowne Partners.

Delta has ruled out any subsidy for Virgin Atlantic, claiming on 22 April that it had its own cash crisis, and adding that it was restricted under the terms of a rescue package by US authorities from financing foreign affiliates.

Virgin Atlantic was already losing money before the pandemic hit but was reportedly making progress under chief executive Shai Weiss. Nevertheless, an application to secure funds under the government’s CCFF was rejected by Morgan Stanley in its capacity as the government’s investment advisor. Virgin Atlantic is not able to access this due to a technicality. Any business which has issued tradeable debt (ie bonds) can borrow from it; but businesses which have not issued tradeable debt cannot.

Sir Richard personally is thought to be asset rich but cash poor. A bailout of Virgin Atlantic by the UK taxpayer would be portrayed in the UK media as overly generous to a very rich man at a time of widespread hardship − and would therefore be controversial. The supposition must be as this goes to press that Virgin Atlantic will fail – though nothing is certain in this environment.

International Airlines Group (LON:AIG)

AIG is of course the London-listed holding company which owns British Airways, Iberia and Aer Lingus. In analysis published on 11 March – before the full impact of the coronavirus epidemic became apparent – UBS tipped IAG as one of the strongest players in the industry, with the highest EBITDA and a substantial cash pile which is likely to get it through this extraordinary period of business interruption. That cash pile arises thanks to three years of excellent profitability. If Virgin Atlantic fails to find a rescue package and folds (which is quite probable at time of writing – though the situation may have changed by the time you read this) then British Airways will emerge as the dominant player in the busy US-UK air lanes. Iberia is already dominant in the Europe-South America network, with an important hub in Madrid.

Wizz Air (LON:WIZZ)

The London-listed Hungarian budget airline announced on 21 April that it had been given the green light by the Bank of England to apply for government-guaranteed debt finance under the UK loan scheme. The airline stressed that its balance sheet is still robust. On 28 April it was confirmed that Wizz Air had been granted a £300m loan facility guaranteed by the Bank of England under the CCFF. With an F3 credit rating from Fitch, the loan facility will carry an interest rate of 0.6 percent. According to an analyst’s report from Citibank in late April, Wizz Air has enough cash in the bank to survive for 22 months without flying.

In late April, Wizz Air announced that it would resume some flights to European destinations from the UK in May, including from London Luton airport. Wizz Air chief executive Josef Varadi suggested that the flights would probably operate half-empty. He also predicted that young people would the first to return to the air and that business travel would struggle, despite the introduction of new hygiene protocols.

Ryanair (LON:RYA)

In contrast to Mr Varadi, Ryanair’s voluble chief executive, Michael O’Leary, insisted in late April that Ryanair would not resume flights until social distancing rules had been relaxed. Mr O’Leary has often embarrassed the airline he has led to amazing heights, with his ‘Trumpian’ utterances. That is one reason (its insensitive customer-service approach is another) why a lot of investors avoid this company, despite its phenomenal success.

Lufthansa (ETR:LHA)

On 23 April Lufthansa warned that it was losing €1m per hour and that it would run out of cash within weeks. The biggest German airline reported losses of €1.2bn for Q1 2020 but said that its losses would be considerably higher in Q2. The company hinted that if state aid were not forthcoming it would go bust in short order. No doubt there will be a bailout of some kind, but how that will be adjudged by EU state bailout rules is another matter.

Cheap oil

One piece of good news for the airline industry is that the price of oil – and thus of kerosene – has hit rock bottom. Fuel costs are, together with airport charges, the main overhead for modern airlines. Reduced kerosene prices will, to some extent, offset lower load factors.

USA to the rescue

The US government has lavished a $50bn package of loans and grants on the country’s aircraft industry. Initial loans carry an interest rate of just one percent and do not have to be repaid for 10 years.

It’s not just the airlines −Airbus in trouble.

If commercial aviation is in trouble – what about the airframe manufacturers? Of these there are two majors − Airbus (EPA:AIR) and Boeing (LON:BOE). The newsflow from the former is depressing. Airbus’s share price has more than halved since well before the pandemic kicked in. This was partly on account of extensive allegations of corruption and bribery on a global scale gaining ground – resulting in fines by the UK Serious Fraud Office and its French counterpart. With the prospect of a downturn in passenger volumes and inbuilt overcapacity in the airline industry, the outlook for airframe manufacturers looks uncertain. This is particularly true for Airbus, for which the A380 Superjumbo was a commercial disaster – even in the good times. On 27 April, Airbus chief executive, Guillaume Faury said in a letter to the giant’s 130,000 employees that Airbus “is bleeding cash at an unprecedented rate which may threaten our existence”.

Outlook

The extraordinary growth of commercial aviation over the last three decades has probably now come to an end. That said, the industry will continue to function even if total traffic declines – there will always be people who are willing to pay good money to travel, whether on business, to visit friends and family overseas, or just to enjoy a holiday. Arguably, the necessity for business travel has been waning thanks to excellent telecommunications: we have all had the experience during the lockdowns of holding Zoom sessions with people located in numerous different countries. There is a mood abroad that most business travel is inefficient and wasteful.

Many people who have been financially disadvantaged by the lockdowns will not have the cash to go for several holidays a year in sunny Spain or Florida. In a sense, air travel may revert to what it was before – a sector catering for the better-off and well-heeled, travelling increasingly on state-owned carriers.

In the era of climate change, air travel has been seen as an increasing source of carbon emissions. Now, the deep-green environmentalists have got what they wanted – travel of all kinds has been suspended during the lockdowns. I am told that one can see the Himalayas from New Delhi for the first time in living memory, so clean has the air become – in a city that was, quite literally, choking to death.

Even if the lockdowns are relaxed sooner than expected, and even assuming that there is no second wave to the pandemic, the upside for the airline industry is tempered by the probability of a protracted recession. The latest IHS Markit European purchasing managers’ index (PMI), where any score below 50 signals economic contraction, showed a record-low reading of 13.5. The worst-hit countries in the eurozone − Italy and Spain − will no doubt wish to reanimate their important holiday and hospitality sectors as soon as possible. But will tourists from the North flock back? Professor Chris Whitty, the chief medical Officer for England, said that Britain would have to live with the virus for “the foreseeable future”: in fact, until a vaccine is widely available or anti-viral drugs are proven to be effective.

The widespread use of contact tracking and tracing technology could ensure that only uninfected people travel – eventually – thus reducing the risk of contracting the virus through air travel. But thus far, that remains for the future.

Conclusion and action

Clearly, some airlines will survive while a number are likely to go to the wall either this year or next. Even some significant state-owned flag-carriers could be abandoned by their governments. As I sign this off, South African Airways (SAA), an important regional player in the African market, looks to be in perilous condition. A reduction in capacity will redound to the survivors who will snap up the business of failed rivals. Overall, the over-capacity that was emerging before the pandemic will be checked.

In the pre-pandemic UBS report referred to previously, the investment bank rated the following as ‘buys’: IAG, Lufthansa, Ryanair and EasyJet. It was neutral on Air France-KLM and Wizz Air. In the US, Delta is of note. Although its fleet has been entirely grounded in April, when Australia re-opens its borders Qantas (ASX:QAN) will be well positioned.

The airport operators are also going to take a hit as volume declines and retail sales diminish. UBS rated Aéroports de Paris (EPA:ADP), the operator of Charles de Gaulle Airport, a ‘sell’. In late April, the operators of Gatwick Airport warned that it may take four years for air passenger numbers to recover. That could prove to be optimistic.

Was there a ‘Golden Age’ of travel? For the industry, in terms of numbers of passenger numbers in spite of hours at terminals and check-ins, probably so. Yet I remember an earlier time when many looked forward to travel by air, when airlines competed at making passengers more comfortable, along with quality meals, occasional free drinks and an attentive service. Well, we know know the answer: quantity seldom equals quality, but we accepted lower standards nevertheless, just as we overlooked a sky peppered with aircraft, polluting the air at 40,000 feet, while inside their narrow shell, ‘squished’ in ever tighter seats among wider fellow passengers, we hoped that time would pass quickly before we came to land… Then terrorism intervened and laxity in aircraft construction brought up an even more urgent question: ‘How essential is Air Travel ?’

A combination of an (even more) unpleasant airport experience, health concerns on-board and higher prices does not make casual holiday travel look appealing, but here’s the killer. You book out of your hotel and find at the airport that, unknowingly, you have a temperature and are thus denied boarding. You can’t go back to your hotel, and given that most will be running temperature checks also, your chances of getting somewhere to stay are… nil. And insurance policies are likely to exclude coronavirus issues. At this point the words “Totally stuffed” come to mind, ass you settle down on a nice comfortable kerbside to be ill for a fortnight – at best. I’m going nowhere until not only do i have a vaccine, but it has been broadly applied. Three years? At best!