Will a rising tide lift all golden boats – or just a few?

Well it certainly won’t float those with a hole in their hull. And many captains (and their backers) will wait to ensure they’re catching the flow and not the ebb tide. So today I canter through those goldies we’ve already explored and some we haven’t and, along with many mixed metaphors, bring up to date my thoughts for a few more miners in the light of a higher gold price.

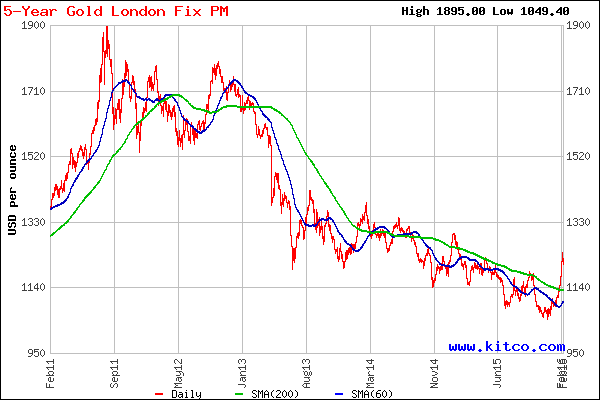

But are we seeing a Neap or a Spring tide? The gold recovery has been significant. There are those who point out that the ‘accepted’ gold price in dollars doesn’t match the supply/demand reality and is distorted by the derivatives – ‘gold’ denominated in paper – that pass for gold in the markets. And I’m not alone in thinking the world economy is so fragile (even without the temporary glitch for frackers, and boost for consumers, caused by oil’s fall) that a flight to gold was always possible. On that logic, gold was on a coiled spring whose latch has been released and is now too far gone to be re-set, so that it seems unlikely this price chart will revert completely to the downtrend it seemed so set upon. If it does it would be erratic and not before a substantial improvement in the US’s soggy economic outlook.

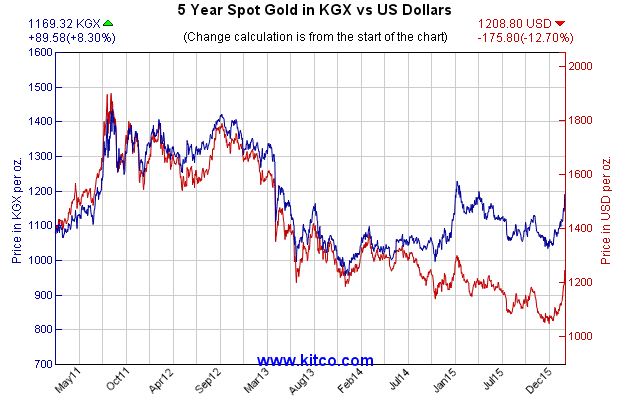

It’s an important point. Gold – recently at least – has acted inversely to the dollar – because it is priced in dollars (as are all other commodities). Kitko’s chart below shows that – priced against a basket of local currencies (KGX) in many of which commodities are produced – gold has not fallen by anything like the same extent it has fallen in US dollars. In the former it is actually ahead by 15% over the last two years. If the local gold miners’ costs are not in US dollars, there would have been more incentive for them to produce or to start a mine than many might have thought. But of course, much of their equipment cost (and the cost of diesel fuel – an important component for many) will still have been in US dollars.

But it shows that worries about a low dollar gold price for the viability of gold mines might have been exaggerated. Even a ‘nil’ Net Present Value might be acceptable to the local and government sponsors of a mine. A zero NPV means that an outside shareholder won’t make a ‘profit’ in the long run. But the local economy will still have received the expected benefits in employment earnings and export royalties; the lenders will have received back their capital and interest; and suppliers will have been fully paid. So there would be no difference in principle from any socialist economy. Even non-socialist governments might sponsor a ‘marginal’ mine and take a bet for the benefits it will bring, hoping gold (or any other commodity) will rise in the long run. What has been holding projects back is the lack of finance, which usually has had to come from outside lenders fixated on US dollars. If local governments or banks were to step up to the mark, the hurdles would be lower.

So, for Kefi Minerals (KEFI) it has been local African development banks that have stepped up, while its recent presentation at the Mining Indaba has helped its shares. Lydian International (TSX:LYD) still hasn’t announced the equity funding that, along with streaming, underpinned my bullish assessment; but the share price has still been strong in anticipation and because the IFC (already a shareholder) has stated that it wants to participate by up to 50%. If it does by some means other than through equity, the result will gear up the return to present shareholders.

Ariana (AAU), whose production profile and essential drilling spending I didn’t like despite an apparently low ‘$600/oz cash cost of production’ has been floating higher, because at $1,200/oz its ‘NPV’ will be a lot higher. ‘A lot higher’ because by how much won’t merely be a direct function of the gold price margin over cash cost alone, but also a function of the Gross PV (the return once the capital cost has been made – i.e. the capex plus the NPV) in relation to the capex. (The new NPV will be the old Gross PV times the new gold price margin over the old gold price margin, less the still fixed capex.) So the NPV will be geared up by more than the price margin improvement. But that doesn’t alter the original reason I disliked the shares.

Since I last commented, Condor Gold (CNR) has indeed pointed to the lending conditions and industry sentiment that I expected its putting itself up for sale last September would demonstrate. No offers have come through, but Condor’s withdrawal from the sale on 18th January and intention to go it alone didn’t produce the further share weakness one would have expected. Instead, its confident tone; its release soon after of significantly improved economics for its La India gold project, whose publication the sale process had prevented; and news that Oracle Investment Management had increased its long-standing stake (along with its 10% shareholder director Jim Mellon), provoked a substantial flurry in the shares. Not that I entirely went along with it, because on my metrics – NPVs at my 8% discount instead of the 5% Condor used – the shares still didn’t look overly cheap, especially at the then lower gold price. However, Canadian broker and adviser Cormark has provided Condor with evidence from a range of industry deals how cheap La India seems to be; and while at present I don’t have enough background detail to persuade me how valid the comparisons are, they are of such interest for the sector that I will comment later if and when we obtain the information.

Hummingbird (HUM), also as we write, has yet to deliver the promised funding that would make its Yanfolila project look attractive at the current share price – more so given a recently announced improvement in its economics. Financier Taurus, however, is taking its time to finalise the deal and has extended its $15m bridge facility – currently being used by Hummingbird to fund preliminary work on the mine and on due diligence – by a further month to 8th March. It is reassuring that Taurus made the following announcement along with Hummingbird; otherwise we might have worried what happens to the bridging loan if the deal falls through.

The lesson that caution is desirable when believing some miners’ plans is demonstrated by developments at Armadale Capital (ACP), who owns 80% of the embryonic Mpokoto gold mine (about the same size, initially, as Ariana’s Kiziltepe mine) in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

As is often the way, what seemed too good to be true is turning out to be not quite so good and so true after all – and by a very substantial margin. Last June Armadale announced that almost all the then upfront $20.5m capital cost would be financed, subject to a forthcoming DFS for which a preliminary estimate showed a $31m NPV8 at $1,250/oz gold – by loans from investors to be introduced by its contractor, Africa Mining Contractor Services.

The prospect of almost no share dilution and the geared returns to be achieved with loans, even at 12.5%, looked extremely good for shareholders. Very roughly, on those figures (excluding potential from further pits and exploration), the present value to be shared by loan and equity providers would have been $20.5m capex + $31m NPV = $51.5m. Deducting the NPV of loan and interest (c. $22.5m) would have left $29m for equity – a juicy 68p/share (54p allowing for the 20% minority) compared with the then 4p share price. But things haven’t turned out that way – by a long way.

Issued shares then 42.8m are now 86.8m, after three fundraisings in six months for £1.5m to progress pre-development. Worse, the updated DFS shows markedly worse economics. Capex has risen 23% while the NPV (again excluding later scope) has fallen to $19m. Even worse, that is now stated at a flattering 5% discount rate whereas the previous, much higher, figure was quoted at a more conservative 8%. And lastly, we are now told for the first time that the NPV is ‘pre-tax and royalties’. The latter, on my estimates, will cost a further $3m, while the 30% corporate tax rate in DRC will cost another 30% of net profit (after depreciation). Without spending time to calculate precisely, we can nevertheless say that – on present shares, and after the only-recently-spelled-out deductions – that original juicy looking 54.4p/share is now more like 14.5p (at $1,250/oz gold). But the company is making much of the potential for later expansion which it says will add another $24m to NPV.

However, it hasn’t spelled out the necessary capex. And after such a drastic downgrade in only seven months who is to say the litany is over?

The shares, however, have held up remarkably well – perhaps because that exceptional outlook last June is still dazzling investors – or else they haven’t updated the sums. (I’m not sure whether the joint brokers have either, because they still, apparently, have 15p and 12p ‘targets’ on the shares – readers will have noted my previous comments about such ‘targets’!)

And that is before even mentioning that the original loan promise was for “up to $20m” for the initial capex. Now that it is $25.2m. Where is the extra $5.2m to come from – if not from further share dilution for a company with a present market cap of under $4m?

The recent announcement from Chaarat Gold (CGH) regarding its planned Kygyzstan gold mine illustrates the key importance for investors of knowing how the four key metrics for a mine impact its value to shareholders. To recap, they are the IRR, NPV, capex, and market value of the shares – all relatively independent of one another so that knowing only one or two won’t help a judgement of the whole.

Chaarat has just published what look like excellent and exceptionally low $635/oz average cash costs to produce 4.7 million ounces over 18 years. However, at $1,250/oz gold the IRR is only a marginally attractive 15.3%. How so? Because the $684m initial capex is very large versus the $116m 8% NPV – which means a longer payback time than lenders will want. In its case, even a high operating margin won’t recoup the capital in a short enough time. So chances are low at present that the mine will happen.

Looking ahead, however, one that will happen and that I plan to cover (because it will come more solidly onto UK investors’ radar later this year) is one of the few operating in the UK (Scotgold (SGZ) is one, and Dartmoor located Wolf Minerals (WLFE) is another) – in the Emerald Isle to be precise.

Dalradian Resources (DALR) is based in Canada but since 2014 has also been listed on AIM (market cap £85m) in advance of expected UK interest in its Northern Ireland gold mine. It is run by Canuks, who, like the Aussies, seem to know more about the mining potential in Britain than many based here. Scotgold and Dalradian know the attractions of the ‘Dalradian’ orogenic gold belt of high grade volcanic gold (and other) deposits that extend from Scandinavia through Scotland and Northern Ireland to Newfoundland (having been formed before, and subsequently torn apart by, the widening Atlantic).

There are other major miners long established in Southern Ireland in particular, but Dalradian has been developing the large – promising to be much larger – high grade Curraghinalt gold mine in Co Tyrone not far from Londonderry. Reflecting the mine’s well above average economics Dalradian has had no trouble raising substantial funds in Canada to progress its exploration and development before the submission later this year of a full planning and permitting application for a hoped-for construction start maybe in 2018-19 (which, apparently, Sinn Fein and the Greens are opposing, although it is difficult to see the N Ireland government turning down such an economic boost).

Thereafter, according to a 2014 preliminary economic analysis (being upgraded to a full BFS by the end of this year) average annual revenues of some $275m (at $1,200/oz gold) will be generating an average $74m annual net cash flow after all taxes and costs over an 18 year life (which stands to be substantially extended according to the exploration potential established so far). During then, the high (over 9 grammes/ton) gold grade results in a well below average cash production cost of only $485/oz, and an 8% NPV after all royalties and taxes of $504m at $1,200/oz gold, against a low $249m capex. Not surprisingly on those figures, the IRR is a solid 36.2% (or 42.9% before tax).

I haven’t yet guessed a share value after funding, but the exceptional economics should flow straight through, which explains why Dalradian has held up so well against the rest of the junior mining sector and why UK investors will be taking an increasing interest in this goldie on their doorstep, and might even be able to visit it. So much more reassuring than investing in some obscure corner of Africa!

Comments (0)