The State of the (Spanish) Union

The Catalonian insurrection has been defeated by the will of Madrid – mercifully without ugliness. But many Catalans are resentful and do not think the struggle is over. Victor Hill has been visiting Spain’s richest province again.

A fairly honourable defeat…

On 31 January, a message sent by Carles Puigdemont, the unlikely exiled President of a free Catalonia, was intercepted. According to the Spanish media, he confessed that his drive for an independent Catalunya was over and that the Spanish national government of Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy had won. The expected national uprising did not happen and Catalonia’s quest for independence has all but ended for now…

Senyor[i] Puigdemont is not a household name in the UK or in the USA. For those of you who have not seen him on TV, he looks like a more nervous incarnation of Bernie Ecclestone though with a more ill-fitting wig. Even his most ardent nationalist supporters will tell you that he lacks charisma.

When Spanish Prime Minister (Presidente del Gobierno) Rajoy imperiously closed down the Catalan Parliament and called regional elections last October, several members of Senyor Puidgemont’s cabinet were arrested by the Spanish authorities for sedition and rebellion (a charge which has not been levied in Britain for centuries). The President of the so-called Catalan Republic had not only declared independence but had also abolished an ancient monarchy and effectively appointed himself head of state.

In response to Madrid’s bellicosity, Senyor Puigdemont scuttled off into exile in gloomy Brussels where he held a number of initially well-attended press conferences before largely disappearing from view. Sensibly, the Spanish government chose not to extradite him from Belgium under the European Arrest Warrant.

Last week the new Catalan parliament opted to postpone indefinitely a vote to re-elect the fugitive President as leader of the region (as Spain would have it) – or nation (as many Catalans would have it). The official line of the Partit Demòcrata Europeu Català (PDeCAT) which Senyor Puigdemont still technically leads, is, however, that he will be re-appointed at a later date.

Roger Torrent i Ramió, the pro-independence President of the Catalan Parliament, said at a press conference on 30 January that there would not be a vote until he has “guarantees” from the Spanish government. Senyor Torrent announced defiantly that the only possible candidate for the time being is Senyor Puigdemont. This decision has left Catalonia in a state of political limbo which only gives more leverage to Señor Rajoy and Madrid.

If the Catalan separatists cannot pick a leader and form a government in the coming months, there will have to be new regional elections.

Spain’s highest court ruled on 27 January that Senyor Puigdemont cannot be named leader of the region because he is a fugitive from Spanish justice living abroad. The Spanish court affirmed that Mr Puigdemont must be physically present at his investiture in the Catalan Parliament. It also ruled that, were Senyor Puigdemont to return from Belgium, he would have to request permission from a judge to attend a session of the Catalan Parliament.

As long as no regional government can be formed in Catalonia, Madrid is set to maintain direct control of the region. Consequently, it is rumoured that the Catalan independence parties are considering other candidates to lead Catalonia. If the Catalan separatists cannot pick a leader and form a government in the coming months, there will have to be new regional elections. The question, therefore, is which way opinion is shifting.

Catalonia Revisited

I wrote a piece for these pages about Catalonia in the run-up to the (in Spain’s view, illegal) independence referendum of 01 October last year. That piece received a surprising amount of attention. I correctly predicted that the referendum would produce a result in favour of Si! (Yes!). That was clear because those who oppose independence overwhelmingly boycotted a vote that they regarded as entirely illegitimate. The 90 percent Yes! vote was therefore highly dubious. Senyor Puigdemont nevertheless took this very unsatisfactory vote – which had admittedly been interrupted violently by Spain’s Guardia Civil – as a mandate to declare independence.

Needless to say, no foreign nations offered support to Catalonian independence (not even the Scots), though there were mutterings about Madrid’s tactics. When Madrid sent Senyor Puigdemont and his team packing at the end of October they legitimised that move by calling for new elections which took place on 21 December. In those elections, the pro-independence parties won out by a narrow margin.

Don’t miss Victor’s next piece in the next edition of Master Investor Magazine – Sign-up HERE for FREE

In the new Catalan Parliament, Senyor Puigdemont’s party has just 34 out of a total of 135 seats and is not even the largest party. Unlike in Scotland, support for independence in Catalonia is fragmented across several pro-independence parties which have differing degrees of bias to the left. The aggregate votes cast for all-out pro-independence parties amounted to 55 percent (if you count the somewhat equivocal Socialist Party as anti-independence). These pro-independence parties command between them 78 seats against just 57 seats for unionist parties.

It should be noted that the Catalan branch of Señor Rajoy’s ruling Partido Popular was thrashed – not that they were ever very popular in modern Catalonia. They fell from 8.5 percent of the vote in 2015 to just 4.2 percent of the vote in 2017 and were down from 11 seats in the Catalan Parliament to an ignominious 4 seats. Señor Rajoy must envy Mrs May the 13 seats (out of 51) that the Tories won in Scotland last June.

In contrast, Ciudadanos (Citizen’s Party), which won the Catalan elections fair and square, is knocking on the door of Señor Rajoy’s official residence in Madrid, the Palacio de la Moncloa.

Table 1: Outcome of Catalan Elections of 21 December 2017

| Political Party | Leader (in Catalonia) | % votes cast | Seats won | Stance |

| Citizens’ Party | Inés Arrimadas García | 25.4 | 36 | Anti-independence |

| Junts per Catalunya | Carles Puigdemont | 21.7 | 34 | Pro-independence |

| Republican Left of Catalonia | Oriol Junqueras | 21.4 | 32 | Pro-independence |

| Socialist Party of Catalonia | Miquel Iceta | 13.9 | 17 | Anti-independence but pro-autonomy |

| Catalunya en Comú – Podem | Xavier Domènech i Sampere | 7.5 | 8 | Pro-“Self-determination” |

| Popular Unity – Constituent Call | Carles Riera i Albert | 4.5 | 4 | Pro-independence |

| People’s Party of Catalonia (PP). | Xavier García Albiol | 4.2 | 4 | Anti-independence |

So the nationalist cause has not been decisively defeated in Catalonia, though its onward march has been stalled. But it is Spanish politics at a national level that has been most traumatised.

Ciudadanos – preparing for power in Madrid

Albert Rivera is a Catalan lawyer in his mid-30s who set up a party in Catalonia in 2006 to counter the creeping nationalism of Senyor Puigdemont and others. The party he founded – Ciudadanos in Castilian and Ciutadans in Catalan – is, according to recent polls, the most popular political party in Spain as a whole and seems set to displace the Partido Popular if not the veteran Spanish Socialist Party as well. A recent poll by Metroscopia put Ciudadanos at 27 percent support across Spain – a full five percent ahead of the two established parties[ii].

Politically, Albert Rivera is another centralist, progressive liberal pragmatist who is being compared to Emmanuel Macron and Justin Trudeau. He is apparently against nationalism, populism and protectionism. And he is apparently for the market economy, social liberalism and, of course, Europe.

Spain, like Italy, has a tendency to throw up political parties which embody the mood of the hour. In 2015 Podemos (“We can”) garnered 21 percent of the vote in the Spanish general election. Its platform was as anti-political as Beppe Grillo’s ludicrous Five Star Movement (Movimento 5 Stelle) in Italy. The general stance of the activists of both Podemos and 5 Stelle is one of F*** the political class – which is fine so far as it goes, but fails to prescribe specific policies that deliver solutions to national problems… Anyway, Podemos now seems to be in steep decline.

Albert Rivera accuses Senyor Puigdemont and his ilk of bringing “economic ruin” to Catalonia (a bit of an exaggeration from what I saw on the ground); dividing Catalan society in two (unfortunately true – just as in Scotland) and violating the Spanish constitution (also true, in my view – but partly triggered by Madrid’s intransigence).

Corsica: another secessionist nationalism asserts itself

Meanwhile, not so far from Barcelona, another ancient nationalism is stirring in the Mediterranean. Last Saturday (03 February) thousands of Corsicans marched through the streets of the capital, Ajaccio, demanding “democracy and respect for the Corsican people”. This was ahead of President Macron’s visit to the island which is officially part of metropolitan France with only very limited local autonomy.

Corsica, the birthplace of Napoleon Bonaparte, was annexed to France in 1769 but unlike other French acquisitions it has never been entirely assimilated into French culture. The Corsican language, sometimes described as an Italian dialect, is still widely spoken. Socially, the network of family clans more closely resembles traditional Italy than modern France.

Monsieur Macron was to have unveiled a memorial to the Prefect Claude Érignac, who was assassinated by separatists twenty years ago. The militant separatists laid down their arms in a Good Friday-style deal in 2014 and went on to forge a political alliance with more moderate democratic nationalists. The political party they formed – Pè a Corsica, led by Gilles Simeoni – won control of the Corsican Assembly in December last year with 56.5 percent of the popular vote in the second round.

Monsieur Simeoni has warned Paris of a return to violence in the region if Corsican nationalist aspirations are not satisfied.

The success of the nationalists in the regional elections raised expectations that Paris would agree to make Corsican an official language alongside French, and that it would concede more financial autonomy. There were also hopes that the French state would agree to allow jailed Corsican militants to serve out their terms in Corsica. Another burning issue is that of French people buying holiday homes on the island. (There are direct parallels with Cornwall here.)

Yet when Monsieur Simeoni met the President of the Republic in January, his proposals – according to his own account of the meeting – were rejected out of hand. Monsieur Simeoni has warned Paris of a return to violence in the region if Corsican nationalist aspirations are not satisfied. If elections achieve zero results, then people will conclude that other means are necessary, he warned last week.

This puts pressure on Paris to concede more autonomy – something that the highly centralised French state has always been loath to do. On 07 February, President Macron, speaking in Bastia, conceded that Corsica’s unique identity should be specifically inscribed in the French constitution – but he was unable to grant any recognition of the Corsican language.

The State of the EU – East versus West

While these internal tensions play out in Spain and France, an important cleavage has come into focus in recent months which could have huge implications for the future of the European Union. While, historically, the main fault-line within the EU was between the North and the South – the surplus countries and the deficit ones – the new fault-line is between the East and West.

Four of the Eastern European countries which acceded to the EU on 01 May 2004 – Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia – have formed a political alliance known as the Visegràd Four or “V4” after the town where a protocol was signed after the collapse of the Soviet Union way back in 1991. Visegràd, in Hungary, was a symbolic location because in the Middle Ages the kings of Poland, Hungary and Bohemia met there to discuss their struggles against Vienna.

This bloc has now gained an ideological identity which stands in contrast to the liberal values of Western Europe. Viktor Orbán, the authoritarian but popular Prime Minister of Hungary, has articulated the values of Eastern Europe as “sovereignty, independence, freedom, God, homeland, family, work, honour, security and common sense”. This is self-consciously a rejection of the ever closer union of liberal democracies envisioned by President Macron and others (such as Senyor Rivera).

Don’t miss Victor’s next piece in the next edition of Master Investor Magazine – Sign-up HERE for FREE

The governments of both Hungary and Poland have come in for stiff criticism in Brussels. Mr Orbán was subjected to a crescendo of liberal obloquy when he ordered the construction of a razor-wire fence along the border with Serbia in 2015-16. And last November the European Commission threatened to impose sanctions on Poland in response to Warsaw’s plans to shake up its judiciary. Poland is now under fire for its new Holocaust Law which criminalises any attribution of Nazi crimes to the Polish nation. All this has served only to increase the popularity of Poland’s ruling Law and Justice Party.

Part of the issue is that the Eastern European nations are sick of being patronised by the European elites in Brussels; but even more than that, there is a fundamentally different attitude in the East towards immigration – and specifically Muslim immigrants. To put it frankly, if it is Islamophobia to fear the influx of a group who have different religious and cultural values, then most Eastern Europeans are blatantly Islamophobic.

The good news: the Spanish economy is on the up

The Spanish economy was knocked sideways by the Financial Crisis of 2008 and the European Sovereign Debt Crisis which ensued. Tellingly, Spain’s GDP is now almost back to pre-crisis levels, having enjoyed 3 percent plus growth in both 2016 and 2017. Analysts expect growth to continue at a similar clip this year.

Property purchases in Madrid jumped by nearly 50 percent last year, unlike in Barcelona where the political uncertainty has dampened prices. (For property speculators, Barcelona could be a buying opportunity.) In Madrid, a lot of interest is coming from wealthy South Americans who are moving to the mother country[iii].

Unemployment in Spain and especially amongst the under-30s is still unacceptably high – it is 12 percent in Madrid but much higher in poorer provinces. This unemployment is largely structural and has persisted for a long time. The Madrid stock market index, the IBEX 35, was negatively impacted by the Catalonian drama but is still up by just under 7 percent over the last 12 months. A clear-cut constitutional settlement in Catalonia could buoy the index.

Making sense of it all

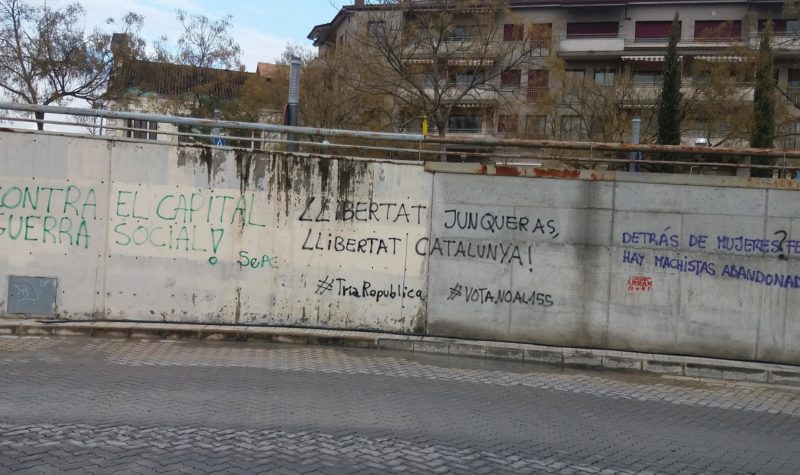

Most support for Catalan independence from Spain comes from mutually antipathetic left-leaning groups and social revolutionaries. But then Franco only took Barcelona in 1938 because the Socialists had fallen out with the Anarchists… I took a photo this week of a display of graffiti at the bus station in Villafranca-del-Penedès. On the left were the usual anti-capitalist memes. In the centre was the nationalist call to arms. And on the right was a statement of radical feminism (ironically in Castilian Spanish). So it is not the case that nationalists are always social conservatives: Catalonian nationalism is right-on modern and ever so European…

It is tempting to reassert the prevailing narrative that big nation nationalism is authoritarian and conservative, if not repressive – while small nation nationalism (Catalonia, Corsica, Scotland) is progressive – red, green and even pink.

But the underlying force which is common to both is that of European political integration – the agenda for which is ultimately controlled by just two key European powers – Germany and France. This Sturm und Drang towards a united Europe has encouraged nations like Catalonia and Scotland to suppose that they could break free of their centuries-old unions within larger states (the Kingdom of Spain and the United Kingdom respectively) without any loss of prosperity.

Brussels’ clear stance that an independent Catalonia would be neither a member of the EU nor of the eurozone was, I suspect, decisive in forestalling the mass protests that Senyor Puigdemont expected. Catalonians regard themselves as more European (and more cosmopolitan) than Spaniards as a whole – they cannot imagine an independent Catalonia outside the EU.

So the EU has given rise to two quite contradictory forces. The centripetal force of imposing sameness despite cultural difference (normalisation is the French term) now meets the centrifugal force of those silly old self-preserving national entities – like Britain, Poland and Hungary – who, so the elites tell us, are hopelessly out of touch with the modern world because they do not wish to lose their identities or control of their borders.

The collision of these intractable opposing forces will sooner or later cause a catastrophic explosion. But I do not think the bang will take place in beautiful Catalonia.

[i] Out of courtesy to Catalan sensibilities I observe the Catalan Senyor for Catalan politicians in preference to the Castilian Señor.

[ii] See: https://www.ft.com/content/8dec6bc0-0a79-11e8-839d-41ca06376bf2

[iii] See: https://www.ft.com/content/ed6daa04-00f7-11e8-9e12-af73e8db3c71

Comments (0)