How to Prepare for Helicopter Money

As seen in the latest issue of Master Investor Magazine

Between a Rock and a Hard Place

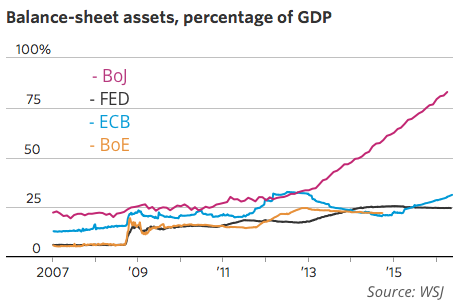

Eight years after the nadir of the financial crisis, interest rates are still near zero in the US and negative in many European countries and Japan. Fiscal policy has quietly assumed a secondary role while central bankers have taken centre stage in dictating economic policy. The proportion of central bank assets to GDP is currently 83% in Japan, 31% in the Eurozone and 25% in the US. Under these circumstances, the financial markets have been turned into a central bank monopoly.

If there’s something worth looking at before investing, it is monetary policy. Central banks today have the power to change prices, coupon rates, dividend yields, and rates of return on every asset on earth.

But at a point where the price of assets already seems high, and most of the developed world is still submerged in weak economic conditions and low consumer inflation, investors need to analyse the available options carefully. On the one hand, not taking risks means having to pay for the privilege of lending money – as would be the case when investing in German or Swiss government bonds. On the other hand, taking too much risk means purchasing overvalued assets, as current prices can no longer be justified by fundamentals alone. The S&P 500 trades on a CAPE (Shiller Cyclically-Adjusted Price Earnings) ratio of 25.6x, which is more than 50% higher than its historical average. Central banks have put investors between a rock and a hard place.

Fighting the Global Crisis

Consumer confidence and investor sentiment in the US was elevated for the greater part of the 1990s and 2000s.

Between 1996 and 2004, the US current account deficit increased from 1.5% to 5.8% of the country’s GDP. For that to be possible, the country had to borrow large sums of money from abroad. But with the global economy doing so well, it was relatively easy to attract funds from an emerging China, from oil exporting countries and from many emerging markets. Their savings were high and their will to purchase US assets even higher. This allowed the US to keep low interest rates while external debt was rising. The inflow of money went in the direction of every type of asset, in particular houses. Between 1998 and 2006, the price of the typical American house increased by around 125%. There was a great deal of optimism and a positive feedback loop was created. The more house prices rose, the more willing to lend money financial institutions became. Everyone was looking for a share of this prosperous market. The optimism was so high that borrowers were always able to refinance their mortgages at lower rates and/or take second mortgages to free up some funds for consumption. As a consequence, the leverage taken in the economy increased significantly.

After 2005, the FED started increasing interest rates and economic conditions deteriorated a little. House prices stagnated. As leverage was previously taken to its limits, many were those who only embarked on mortgages because they thought they would be able to refinance them in the near future at lower rates. But with house prices stagnating that was no longer possible. As a consequence, bad loans shot up and created trouble for many financial institutions. Faced with liquidity problems, these institutions stopped lending money to the economy, including to businesses. By then, the central bank had to assume its role of lender of last resort because the market mechanisms weren’t working properly. The distrust among banks was so high that the rate at which banks lend to each other spiked. The FED cut interest rates and provided the necessary liquidity to avoid a systemic crisis.

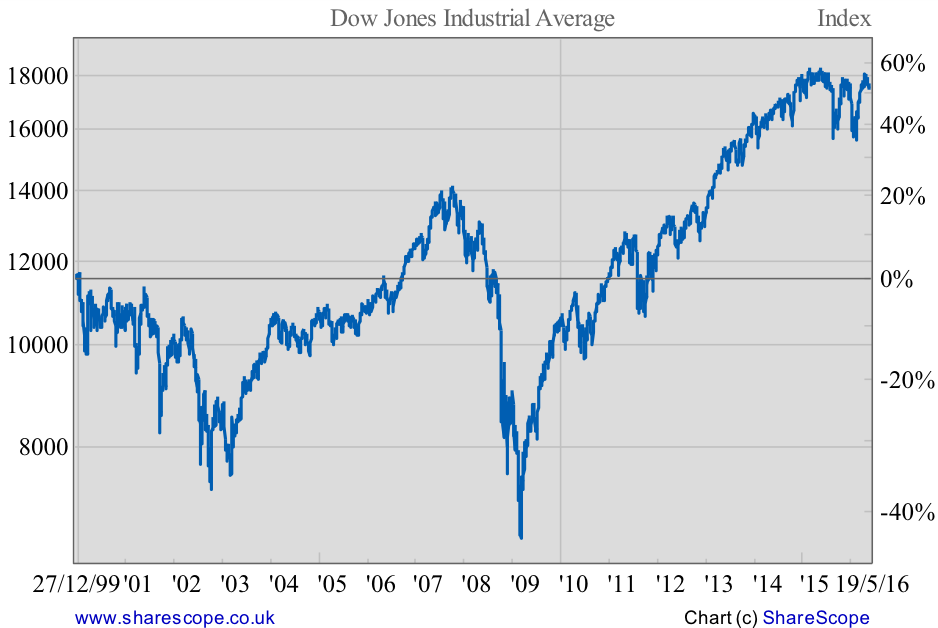

The collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008 scared everyone. The Dow Jones index, which peaked above 14,000 points in October 2007, quickly saw 7,400 points wiped off its value, to hit 6,600 points in March 2009. By then, Ben Bernanke had no option but to implement quantitative easing, as a way of improving asset prices and breaking the downward spiral.

From a Necessity to a Paranoia

It is hard to argue against central bank intervention when systemic risks are on the table. But as soon as liquidity conditions are restored, the best idea is to allow the banking system to do its job. Otherwise, we should have conceived a planned economy without private banking at all. Alas, after restoring confidence, the FED insisted on extending quantitative easing, unfolding a second and a third round of asset purchases while keeping interest rates near zero until December 2015.

More than seven years after the crisis, the Dow trades at 17,500 points, which is 25% above its pre-crisis peak and 165% above its crisis nadir. Still, the FED seems unable to hike its key rate, as it is paranoid about the effect that such a hike may have on the equity market.

Central bankers are convinced that deflation leads to weaker economic conditions and that the best way to increase prices is through quantitative easing. For them, everything hinges on the equity market. I can accept the deflation observation (with a grain of salt), but not the quantitative easing connection with prices. Quantitative easing certainly generates asset price inflation but doesn’t need to lead to consumer price inflation. For the second to happen, it is requisite that higher asset prices lead to more investment and hiring and then contribute to an increase in real wages, an increase in household income and finally an increase in consumption and prices. That’s a long transmission mechanism that may or may not work in the expected way. Looking at past experience, it seems that it didn’t exactly work that way at all. Higher equity prices led companies to pay higher dividends, to repurchase their own shares, and to embark on mergers and acquisitions. Faced with a weak consumer, companies had no urge to expand their businesses. There was certainly some hiring, as reflected in the improving jobless rate, but the majority of the impact on prices has been via assets rather than consumption goods. That’s why we don’t have consumer inflation at a time when the expansion of the money supply has been substantial.

Central banks around the world followed the FED in expanding their balance sheets, mostly without any success in restoring inflation levels. Instead of realising that pass-through didn’t work in the predicted way, they convinced themselves that bolder action was needed. They then broke the limits observed by academic theory, and challenged the zero lower bound, by pushing interest rates into negative territory. The reasoning is straightforward for them: lower financing costs and high liquidity availability should drive asset prices higher and boost investment, hiring and finally consumption. But, once again, it failed, as households are not feeling the stimulus and/or they’re not willing to spend it. It seems that the lower the rates are, the more households are willing to save and then the worse the situation becomes in terms of consumption.

Creating a Distorted World

Jim Mellon made a fantastic, and somehow shocking, observation at the Master Investor Show. He claimed that central bankers all come from academia, and often sport a stint at Goldman Sachs on their CV. (For those of you familiar with Goldman, its record at making predictions is less than enviable, despite its supposed prestige.) They will likely end up depleting our economic resources and interfering with our retirement plans. Jim also noted that many years ago people were able to get a 4% return on their capital over the long run. With 3% being consumed, 1% was left for compounding. But today the situation has changed so dramatically with negative interest rates that all a saver is able to achieve is capital depletion over time, which forces him to save even more. Central banks have thus hamstrung savers and turned investment into a “boring” activity.

Years of desperate central bank intervention have led to severe economic distortions. Due to low interest rates, capital has been misallocated into capital goods instead of being allocated into consumer goods; asset prices have lost their link to fundamentals and are leading to price bubbles; savers are no longer able to save for their retirement; consumers are gripped by a sense of pessimism that has been created by excessive central bank intervention; companies have increased their debt exposure without a corresponding increase in investment; banks have seen their financial position weakened due to an erosion in net interest income; and central banks have spent all their ammunition and approach the next crisis empty handed.

They Won’t Stop

But just because monetary policy has been ineffective so far, it doesn’t mean central banks will stop. On the contrary, they will most likely experiment with new tools until the final consequences bear out. Next in the queue is ‘helicopter money’.

Many years ago, Milton Friedman created the concept of helicopter money to explain how the money supply process works and how inflation is generated. Today, the concept has been reinvigorated and will gradually be adapted as an alternative central bank policy to fight deflation. The logic behind helicopter money is simple: if the government or the central bank were able to drop money from a helicopter to the population, then, as people spend the money, inflation would certainly been generated. In the real world there won’t be any helicopters but rather a monetisation of government debt by the central bank via direct purchases of newly issued debt from the government, or a direct distribution of cash to the public. So, as Jim Mellon mentioned in his Master Investor presentation, central banks (in particular the BoJ) may start giving consumption vouchers to households for them to spend the money.

While central banks deny contemplating the use of such policies for now, the idea will become more popular in the central banking community as they continue to obsess about generating inflation. With this in mind, the worst thing an investor can do now is purchase long-term government bonds at their current yields. Investors should short these bonds instead (in particular those from the German and Swiss governments), as they won’t cover inflation. Purchasing long-term bonds at yields below 2% is the same as betting against the ability of a central bank to achieve its inflation goal. With central banks expected to boost their money supply in one last attempt to generate inflation, the best bet is to short cash and bonds. As an alternative, investors still have equities. But many equity markets now look overvalued and thus do not present a favourable risk/reward ratio.

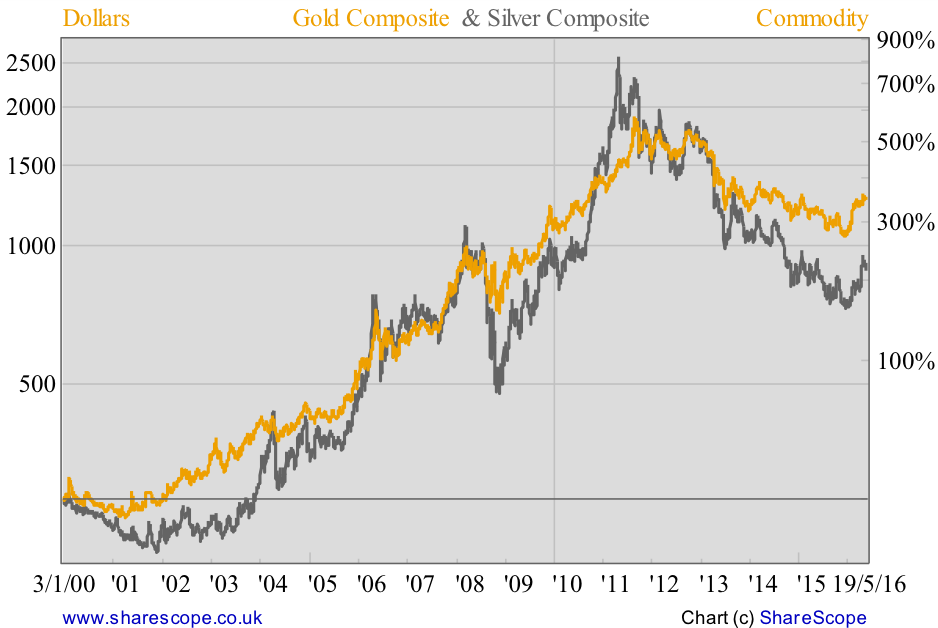

It is time to be selective when choosing equities and to look for alternative hard assets offering intrinsic value on a limited supply. Precious metals, in particular gold and silver, are a perfect fit here. Some people argue against gold as an inflation hedge, but I believe that under the current economic conditions where uncertainty about the future is huge, the opportunity cost of holding non-interest bearing assets is near zero (if not negative), and the money supply is expected to boom, gold and silver look shiny enough to add to a portfolio. In the meantime, while interest rates are negative, gold still looks like a very good alternative to EUR 500 and CHF 1,000 notes.

How to Gain Exposure to Precious Metals

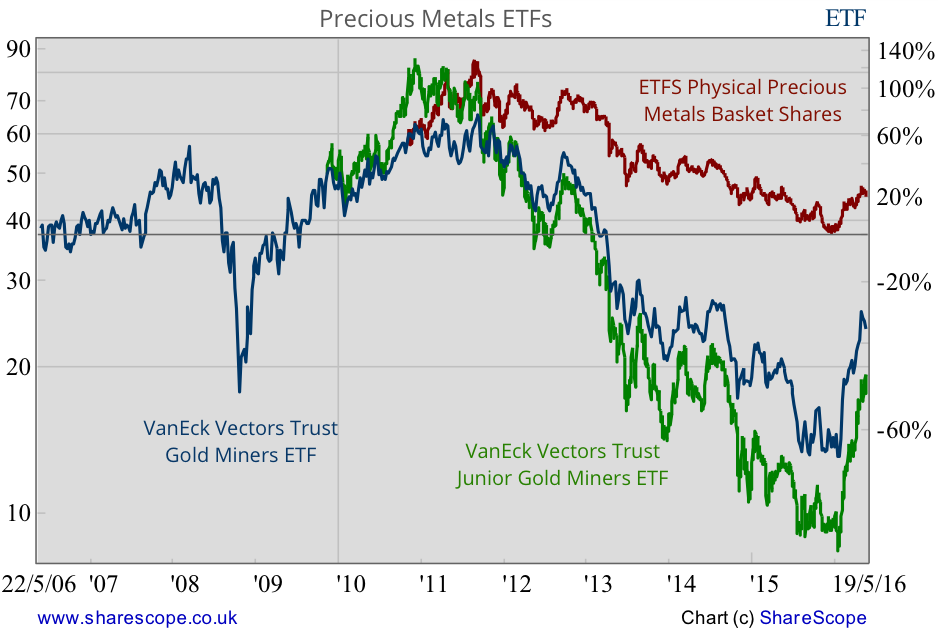

There are many ways of getting exposure to the precious metals markets. Investors can always purchase the physical metal, which is probably the safest option of all, as it allows for the retention of the physical asset. But that option implies some carry costs that include safety, storage, and other costs. A cheaper option would be to purchase physical gold through an exchange-traded fund. The SPDR Gold Shares ETF (GLD) holds 100% physical gold bullion. To get exposure to silver, investors can purchase the ETFS Physical Silver Shares ETF (SIVR) which holds 100% physical silver bullion. A mix of gold and silver can be achieved with a stake in the ETFS Physical Precious Metals Basket Shares ETF (GLTR) which holds gold bullion (58%), silver bullion (30%), platinum bullion (6%) and palladium bullion (6%).

For those willing to make a leveraged bet on the price of gold, an alternative way is to purchase gold miners. To avoid the idiosyncratic risk deriving from concentration in too few companies, one way of achieving an efficient exposure would be by investing in the VanEck Vectors Gold Miners ETF (GDX) or in the VanEck Vectors Junior Gold Miners ETF (GDXJ).

Comments (0)