Why this election is the most important in a generation

The December General Election will arguably be the most important in our lifetime. Its implications, both economically and politically, will be profound, argues Tim Price.

“Hoping for a really FILTHY election campaign. I want to see proper threats, lawsuits, dirt, blackmail, galactic class hypocrisy, rent boy scandals, closet skeletons, the lot. Fleet Street, do your JOB.”

– Tweet from Old Holborn QC (@Holbornlolz), October 30 2019.

The great economist, Adam Smith, once remarked that there’s a great deal of ruin in a nation. The full context of his remark is intriguing. He was replying to a correspondent reporting on news of General Burgoyne’s defeat at Saratoga in late 1777. The correspondent feared that Britain’s war effort in America promised calamity, and Smith’s stoic response was designed to settle his nerves.

But once a country definitively hits the skids, it can be a long slide down. Argentina, for example, was, at the start of the twentieth century, one of the wealthiest countries in the world, blessed with an abundance of fertile agricultural land. But once a military junta seized power in 1930, the jig was up. Chronic political instability and a succession of incoherent economic policies created a ‘basket-case’ economy whose government would ultimately default on its debt nine times following its independence from Spain − three times since the turn of the millennium.

So, as we head towards one of the most fractious general elections in our country’s recent history, there is some cause for concern. The die in favour of free-market capitalism was not definitively cast when Margaret Thatcher turned back the socialist tide in 1979. The country could yet take two steps backwards to the miserable economic conditions of the 1970s.

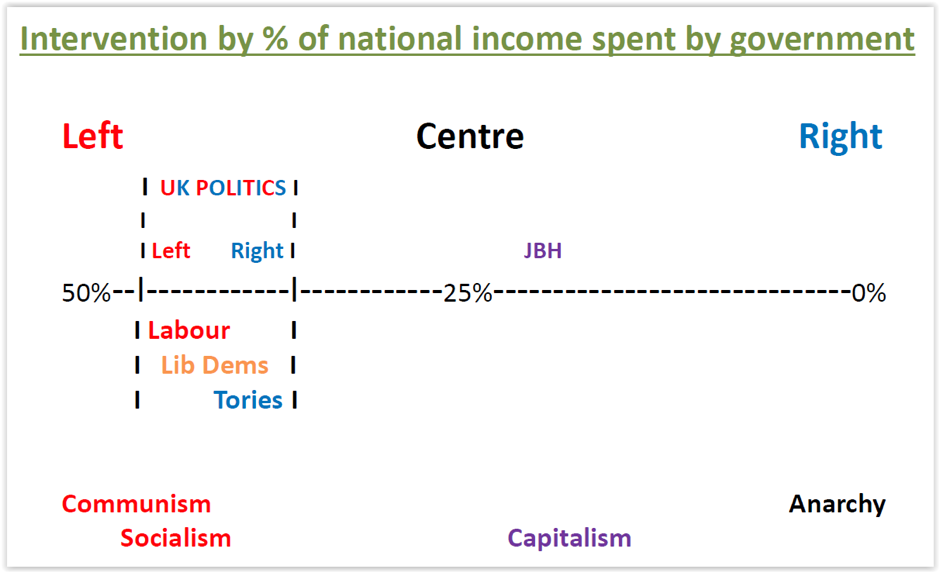

Indeed, for all the headline-making bluster of the three main British political parties, they have more in common economically than meets the eye. I am indebted to John Hearn of the London Institute of Banking and Finance for his enclosed chart, which highlights just how similar the ‘tax and spend’ policies of Labour, the Lib Dems and the Conservatives actually are. Each major party has pledged to spend something approaching half of our country’s GDP on forming a government. John’s own preference for government spending is just under 25% of national income, as denoted by that lonely looking ‘JBH’ on the chart.

Source: London Institute of Banking and Finance / John Hearn

It wasn’t always like this. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the UK government was only spending approximately 10% of the nation’s income. Then came two world wars and a long period of national decline, arguably reversed only by the ‘shock economics’ of the Thatcherite free-market revolution. Nevertheless, subsequent Conservative governments have shown no obvious enthusiasm for either balancing the country’s books or taking the foot off the spending pedal.

It is as if all of our political parties have forgotten – if they ever even knew – how wealth is created. Without the risk-taking of the entrepreneur, there is no capital for government to redistribute in the first place. And there are only three ways of spending money. One is to spend one’s own money on oneself. Such spending will likely be done well. Another is to spend one’s own money on other people. Such altruistic spending will also likely be done well, and at least on a targeted basis. The last way is to spend other people’s money on other people. That is what government does, and it is invariably done badly, and with unintended consequences.

In the absence of the prolonged torture of another hung parliament, we will soon know the composition of a new government, and perhaps the likely fate of a country struggling to free itself from the European Union – a classic example of Big State economics if ever there was one. The existential co-mingling of Brexit and a clear Conservative majority in parliament is what makes this December general election so critical for the country’s future. An electoral failure to deliver both cleanly has a good chance of jeopardising our country’s economic prospects in a profound way.

One of the stranger aspects of Brexit coverage within Britain’s mainstream media has been the almost complete absence of any commentary about the failing nature of the eurozone’s financial system. Analyst Russell Napier has been one of the few to point out the transparency of the EU ‘Emperor’s new clothes’. It was Russell, in August 2019, who highlighted the danger of the eurozone’s Bank Resolution and Recovery Directive (BRRD), which was enshrined in eurozone law back in 2014. The BRRD explicitly removes any guarantee for large-scale banking depositors. It does, however, ensure that large-scale depositors at a failing eurozone bank will be bailed in as required in any future ‘recovery’ action.

The BRRD helps accounts for institutional investors taking money away from German banking groups, for example, and reinvesting that capital in German government bonds. It is not because they have any great enthusiasm for negative yielding German government bonds, but primarily because they fear the consequences of a German bank becoming insolvent (the name of Deutsche Bank usually features at this point of the conversation between European financial gossips). It all comes down to counterparty risk. As Russell points out, there is a way of describing money being taken out of banks for fear of appropriation, and of losing it, in part or in whole. It is called a bank run. And it is already well under way in the eurozone. Still keen on ‘Remaining’?

One of the reasons I have been such a passionate ‘Leaver’, both before and especially after the June 2016 referendum, is that I believe in democracy. But I also believe in sound economics. For me, the economic arguments trumped all others. Yes, there will inevitably be some short-term pain as the UK reconfigures its trading relationship with the rest of the EU. But that short-term pain has to be balanced against the opportunity of negotiating free-trade agreements with those parts of the world growing far more quickly than the eurozone. (There’s a reason why the fund I co-manage has the lion’s share of its investments in Asia.) And it also has to be weighed up against the long-term cost of having to participate – on an involuntary basis – in a bail-out (or even worse, a bail-in) of failing eurozone banks and financial institutions brought to the brink of insolvency in no small part by the ECB’s monetary policies.

The democratic aspect of Brexit cannot, however, be overstated. Over three years ago, the UK as a whole voted to leave the EU. This was in the face of massive opposition from the Establishment, including the government of the day, the Bank of England, the US president, the IMF, the TUC, the BBC and just about every firm in the City of London. You cannot decide not to implement the outcome of a legitimate vote just because you happen to disagree with it after the fact. Only banana republics do that. For this reason, I have nothing but contempt for the official Brexit policy of the Liberal Democrats. Labour is not much better, with Jeremy Corbyn having sat on the Brexit fence for so long that the iron has entered his soul. And the less said about Labour’s economic policy, the better. In any case, John Gray, the British philosopher, writing for The New Statesman on Brexit earlier this year, points out that the debate transcends ‘mere’ economics, and gets to the heart of what moves people politically and emotionally:

“The British political classes have made the same mistake that Keynes ridiculed in his early self. They have failed to understand some of the most powerful human needs. If a majority in Sunderland continues to support Brexit despite the threat it poses to Nissan expanding its operations in the area, the reason can only be that they are irrational and stupid. The possibility that they and millions of others value some things more than economic gain is not considered. Persistently denying respect to Leave voters in this way can only bring to Britain the dangerous populism that is steadily marching across the European continent”.

So, the outcome of this election really does matter for the future of the UK, both democratically and, especially, economically. I speak as a believer in democracy and free-market capitalism, and as an investor. Money goes naturally to where it is most respected. Take it for granted, or treat it with contempt, and it will go somewhere else. If, as a by-product of our general election, Brexit is thwarted, or overturned, or watered down as to make it essentially pointless, the implications for our political and economic future are grave. I have no wish for Britain to emulate either Argentina or Zimbabwe.

Sadly never a balanced viewpoint from these writers.

They all appear to be somewhere to the right of Genghis khan.

Hopefully you will be very disappointed tomorrow.

This article is excellent.

I am particularly disappointed that the press, and particularly the BBC, have said so little about the failings (financial and otherwise) of the EU; its progress towards a post-democratic era and the 2.5+ billion euros written off each year.

I can only say” SPOT ON” ,never a set of accounts from day one from the

EU. I wonder where the 2.5 billion write off s go,thank god we will soon be shot of them.

kind regards.